Elowyn Collins

©Christine Shields, 2022.

Page from Elowyn’s baby book from Chenzhou Children’s Welfare Institute, 2002. Courtesy of Elowyn Collins.

Elowyn Collins is 20 years old and is living and working on the East Coast the autumn and winter of 2022. At Portland State University, she is a junior majoring in international global studies with an Asia region focus. She was adopted from Chenzhou Children’s Welfare Institute (CWI), in Hunan Province, in May 2003.

Alex met Elowyn through a survey Elowyn had posted through Brian Stuy’s Research China site. His organization helps adoptees research their finding ads and other primary documents, and learn about the process of birth parent searches. Alex interviewed her in May 2022. The interview has been condensed and edited.

“I’d ask [my parents], ‘Why was I abandoned? Didn’t they love me?’”

Alex: How did you find out about Brian Stuy?

Elowyn: I watched the Amazon documentary One Child Nation, and that’s where I found Brian. I got his birth parents’ search analysis and copy of the finding ad in the newspaper.

You were adopted as part of the surge of Chinese adoptions, which crested after 2005 or so (which is when we adopted Eli).

Yeah, it was during the SARS epidemic.

Why did your parents decide to adopt from China?

My parents always told me they liked the food and the culture. But in terms of SARS, the government was closing up international adoptions to limit travel. My parents traveled with one of the last groups to go in before they closed everything. When I came home, at the airport, a local Portland news station did a brief segment. People were like, “Oh my God, you’re going to China during the SARS epidemic?” And my mom’s logic was that if it wasn’t safe for us to be there, it’s not safe for her. So they felt it was really important to get there.

Once we got the referral information on Eli, it felt really anxious to wait. You want to have your baby in your arms. How long were they in China?

They didn’t visit the orphanage. They stayed in the capital of Hunan, Changsha.

You were in an orphanage connected to the United States nonprofit Half the Sky, as Eli was, that trained nannies to attach and nurture babies. After we adopted him and I learned about the Hunan scandal, I felt like we didn’t have the right story about Eli—and we might never know. I asked my contact at the adoption agency and I asked our guide in China, who’d moved to the United States. They didn’t give me any information. I contacted Half the Sky, too. It was making me really upset, not knowing. I felt like Half the Sky, they’re Americans, and they should honor the child’s background. They’re facilitating nannies bonding with the infants. I’m sure they know more than they’re saying.

I definitely think it was interesting, like if they were supporting what was happening, especially in Hunan [which had documented baby trafficking, unlike in Eli’s province]. They had to be aware of something. There was a lot of baby trafficking going on. People were getting babies from other nearby provinces and bringing them to Hunan. So technically any of us could really be from a different province.

We gave a $3,000 donation to the orphanage; that was standard. To me that was totally fine because they’re taking care of this beautiful child and other children who would otherwise not have a home. Do you know the motivation for the infant trafficking?

You should watch the movie on Amazon. It’s amazing. It’s very emotional. I would not recommend watching it late at night. If your son wants to watch it, you might want to be there for him. It was very touching for me. It talks about how orphanages would pay the people who brought babies to the orphanage because they actually profited quite a bit off of international adoption, which is why it was such a popular market. So they are getting a cut, because you pay thousands of dollars to get all of this done and everything’s pretty orchestrated. I just know they profited off a lot from international adoption.

Elowyn: “It’s silk art that my parents got for me when they traveled to China to adopt me. I’m the year of the horse.” Courtesy of Elowyn Collins, 2022.

When you were growing up, your parents were immersing you in Chinese culture through schooling? Were you aware you were different from kids who had Asian parents or was that hard to understand for a while?

That was my normal. I didn’t really compare it. Part of the reason my parents adopted me from China was the Mandarin immersion program in Portland, and they wanted me to be around Chinese culture and have Chinese teachers and understand the culture outside of Chinese restaurants. They’ve always been supportive of me learning my Chinese heritage.

Do they have any Chinese friends? Chinese American friends?

I don’t know. I know a family friend who adopted from China. She was Caucasian and she adopted a baby from China.

Do they have any Chinese American friends or any Asian friends?

I think my dad had one growing up, but I don’t really honestly know.

I interviewed a friend of mine named Lincoln who grew up in Iowa, and he was adopted from Korea, and he feels that transracial adoptions are problematic because of the alienation.

That’s something that I thought about, but I feel loved, protected, and supported in the family. I haven’t had an identity crisis, but I was in the Mandarin immersion program. I have good friends who are Chinese adoptees. I could connect with those people as I was learning the language as well as the culture of China. It was actually the best I could get considering I was adopted by Caucasian Americans and I’ve lived in Portland my whole life. I didn’t realize how white Portland was until I went to San Francisco. I was in an environment where I saw other Chinese people every day at school.

Do you have any siblings?

No, my parents had infertility issues. So that’s how they came to adoption.

How did you first discover serious issues with the Chinese adoption system? Do you remember what your feelings were like when you first started reading about child trafficking?

I knew about China’s one-child policy, but I wasn’t really aware of the corruption that was going on, at least not the nitty-gritty details, until I watched One Child Nation. Because they talked a lot about the trafficking and how the government dealt with families who had more than one child. It really hit home when they mentioned Hunan, because that’s where I’m from. And I wasn’t aware of the scandal. It was mind-blowing. I’ve researched the one-child policy, but I’d never really heard about the corruption that went on behind the scenes. I’d accepted my finding story that they told my parents. I had accepted that blindly. I never questioned it until I watched One Child Nation. And that’s how I found Brian [Stuy]. My parents had found him in 2003 to do the finding ad, but I reached out to Brian about the report and he found holes in my finding information. Like the name of the hospital listed is in a different city than the one listed in my documents.

Souvenir baby image of Elowyn from China. Courtesy of Elowyn Collins, 2022.

Eli’s story was that he was dropped at the gate, and I thought it was so emotional. I’d made up a story about the mother leaving him, because his papers state that the watchman at the gate found him. You know, there’s no way someone can leave a baby there. And my dad, who went with us, got a rock from near the gate to symbolize the last place Eli’s mother saw him. It could be just a big lie.

Yeah, that’s what was mind-blowing. I’ve been researching this, but I had never heard about it before I watched that documentary. It came out in 2019.

Were you mad at your parents for adopting you from China, considering the corruption that’s come to light?

No, I’ve made peace with it. I can’t do anything about it. I don’t know what my life would have been like if I wasn’t adopted. I feel no anger toward my birth parents or my adoptive parents. It is what it is. I’m happy where I am.

When Eli was a baby he never brought up his birth father, but he had a lot of feelings about his birth mother. It was heartbreaking.

In my survey, there is a question at the end for the parents and for the adoptees themselves. “What do you wish you could tell your birth family?” They always mention the mother but only two responses mention the father. I chalked it up to the mother-daughter bond, but I don’t know.

Is there a story about the objects you chose, the baby journal from your nanny? Do you feel you had bonded with those nannies? Do you have a loss there?

Yes, but it’s kind of subconscious. I was adopted at eight months so I don’t have any memories of that. What is cool about the journal is that because I studied Mandarin for so long I could read it without a translator. That added to the meaning: that I was able to read it by myself. What was disappointing was that my nanny was sick and unable to come to the hotel where the travel tour was.

We had a really small group, us and another family, and two sets of grandparents, my parents and then another set. And our guide. So we went back to the orphanage with the babies after we adopted them and brought back gifts. The nannies could see them one more time.

The nannies came to the hotel where the travel group was. They were in a conference room and wrote everyone’s name out. And that’s how they did it. They didn’t go to the orphanage.

Self-portrait. Courtesy of Elowyn Collins, 2022.

Have you been back to China?

I’ve been back to China. but I didn’t go with my parents and I didn’t go to the province I’m from. In the Mandarin immersion program in Portland public schools you go on a capstone trip in eighth grade. You travel to China for two weeks. That was a very life-changing trip. I don’t know if it is because it collided with the transition between eighth grade and high school, but I was very impressionable. I found a sense of belonging when I went to China even though I wasn’t in my province. It was very powerful to be like, “Oh my gosh, look, there’s so many Chinese people around me. I can communicate with these people and they have no problem understanding what I’m saying.” I’ve been around Chinese culture for as long as I can remember. I’ve always grown up around Chinese people studying Chinese. So, I’ve always wanted to find my birth family. I didn’t actively start searching till March of 2020, but it’s always been something I’ve wanted to do. Going back to China just felt like a natural step.

Did you ever make up stories about your birth family? Like, wonder about them when you were little?

Yeah, I’d wonder about it. I’d ask, “Why was I abandoned? Didn’t they love me?” My parents always told me, “They left you in front of the hospital so they know that you’d be found and you were loved” and all that. I became attached to one Chinese teacher, because I studied with her for four years. She helped me picture my mom, my Chinese birth parent. I never clearly quite knew what resources I had until March of 2020. One Child Nation sparked me to actively search.

What did you have from China? Did you have just basically the clothes you were wearing? There was no finding note, I guess.

Right. There is no finding note, but my parents kept the outfit that I was in when they got me.

Are your parents supportive of you searching for your birth family?

Yeah. They’ve always just wanted my birth parents to know that I’m loved and then I’m healthy and I’m safe. They got me the 23andMe test as a Christmas present one year because I really wanted it.

I’ve heard that only 10% of children in orphanages were adopted internationally in China, but that might be wrong. But there is an inherent flaw in taking a child from their culture and then the corruption that’s come out.

My parents thought about that a little bit. Your feelings are like a lot of adoptive families, especially if it’s transracial. But are we taking a child from a situation that would have been better? Like, am I taking them from their home culture? I know my parents have been very open about any question I had about adoption.

Do you feel like the institution of international adoption is inherently flawed?

At least we’re trying to respond to the corruption. I don’t know how accurate their estimates are just because of all the baby trafficking and baby buying. Like, a number of children were never registered in China for fear that they’d be taken away. It came out in my research, that people [adoptive parents] weren’t aware of the corruption at the time.

Do you feel like you personally would adopt a child?

I have been on the fence about it. But what I do know is that I plan on having at least one biological child just because I don’t know anyone biologically related to me. I’ve thought about adoption. It feels quite complicated. When you grow up, people might think this is not technically your home culture. I don’t know if that’s something I want my child to deal with, if that makes sense, but I’m not against it. It’s just not in the cards for me at the moment.

What is the next step you’re going to take in your search for your birth family, or your birth mother?

I’m waiting on social media to see if anything pops up. They put my info on the Chinese version of TikTok [Douyin]. They’ve gotten these cool statistics that you can see through the social media company. So I’m waiting on that and I have my DNA on My TapRoot. But they’re closing. And the Nanchang Project helps adoptees find birth relatives in China through DNA testing.

Projects

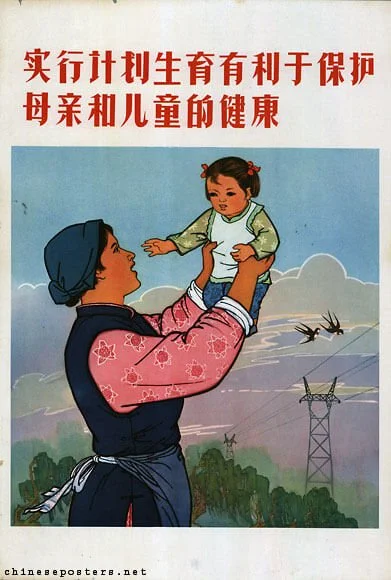

Propaganda poster for China’s One Child policy. Chineseposters.net.

Chinese Adoptees and Adoptive Parents Survey

Elowyn produced a Chinese adoptees and adoptive parents survey, summarized here.