William Smith

©Christine Shields, 2022.

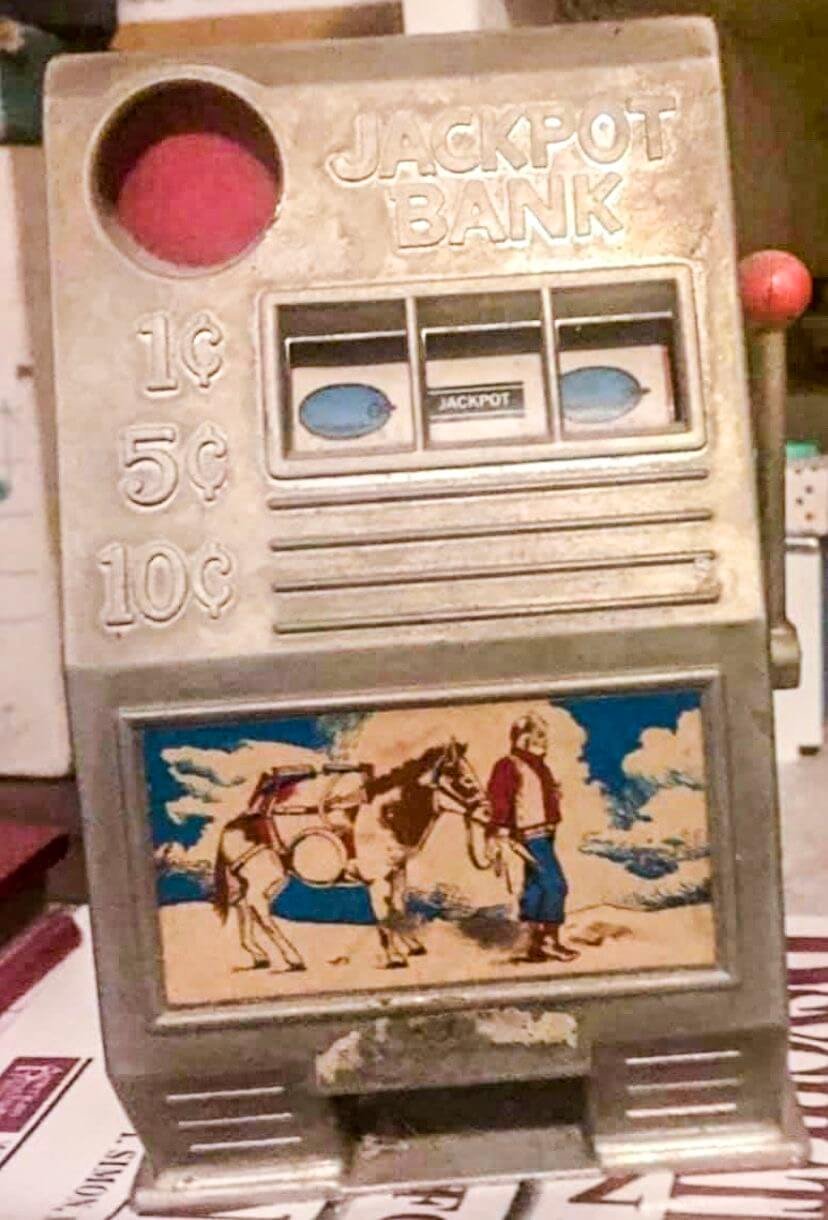

Slot machine coin bank from William’s stepfather. Courtesy of William Smith.

William Smith (Nichols), a 61-year-old retired mailman, was born in Alamogordo, NM, and grew up in West and East Oakland. In the mid-1980s he moved to Berkeley and quickly became integral to the punk, experimental, and indie music scene of the Bay Area and beyond. He’s been a DJ—dubbed “Last Will”—for close to 40 years at the seminal college/community rock stations KALX and KPFA. He’s also a sax player and writer. Will and Lisa Wenzel, his wife, whom he met at KALX, live in Albany, CA with two cat companions, Esmerelda and Beatrice. The interview compiles two phone interviews that are about 10 years apart (the second, in 2021). It’s been edited by Will and Alex.

“Black people roll however they can.”

Alex: This adoption interview project came about because my son, Eli, keeps editing his bedroom, as you do as a kid. At 17, he presents as a typical skateboarder. He doesn’t want to go around saying he’s adopted. He feels Chinese on the outside and white on the inside. But he displays a few objects that relate to him being adopted and being Chinese. So that’s interesting to me: What we keep as talismans. You sent me a picture of a toy your stepdad brought back from Las Vegas. Was it special to you growing up?

William: It’s from my stepfather, John Smith. I was living with my adoptive mom, Beatrice Davenport, who was at the time just my guardian. When I was seven, she suddenly said, “I’m going to marry this man.” It was August 24, 1968. Then they got back from Reno, and I got the toy bank. As a kid I thought it was cool because it was actually a bank as well. It was heavy duty because it was still the late ’60s. It’s tough, it wasn’t all plastic, and you could put coins in it. You pull the slot and if you got a jackpot, the coins would come out.

As I grew older it became kind of a habit, just pulling the thing anyway, like picking a scab. I never managed to lose it, so when I turned 18 and left at 19, I took it with me. Then our relationship [with my stepdad] got more like an adult relationship. He was always much older than me—he was born in 1900. He was 68 when we moved into his house in East Oakland. He later passed away, and I didn’t know about it because his daughter hated our guts. Nobody made the effort to contact me. I felt really sad about that. The slot machine is the only thing I have of his to remember him by. There were no pictures. We didn’t have camera. I have dreams about him—I wish there was a word between nightmare and dream.

It does seem like dreams about dead people are often between a nightmare and a dream because it’s never as satisfying. Like you’re grateful that they’re there, but they lack humor, or they lack something. I listened to the 2014 StoryCorps episode between you and Willie Nichols, your birth mom. It must be hard to listen to it now but precious that it exists.

Yeah. It’s surreal. It hasn’t really sunk in yet: her death, me finding her, all of that. I’m probably in a different place than my siblings for sure. Ultimately, you know, there’s a lot of sadness, but I do have a lot of gratitude at the same time.

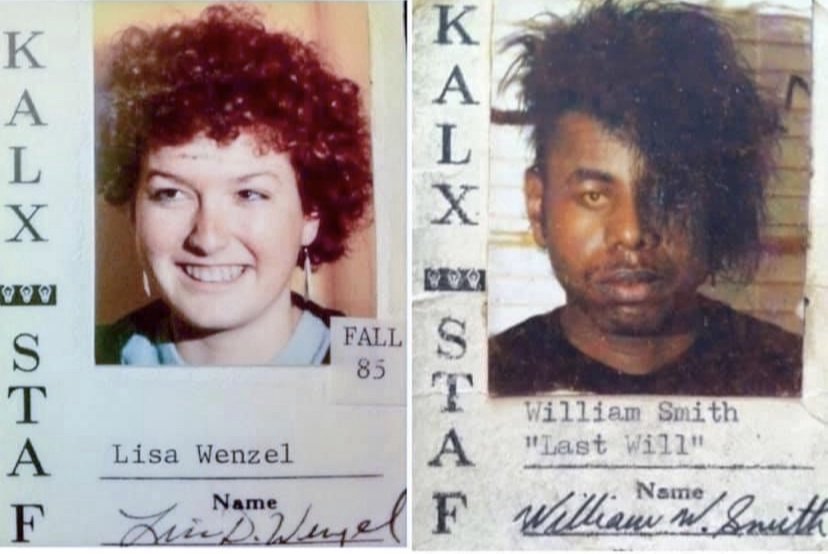

DJ Last Will at KALX, c. 1980s. Courtesy of William Smith.

What year did she pass away?

2016. I know it was February because I was on KALX. I was on the air and the Super Bowl was happening at the same time. I got a phone call from my oldest sister that my mom had died.

Did you know that you were adopted when you were a kid?

I had to figure out. In that era, secrecy seems typical with a lot of adoptions. I didn’t know a lot when I was growing up, because a lot of times children were taught to be kind of ashamed of it. It was a family secret. It just wasn’t really open. My adoptive mom didn’t want me to know that my birth mom had been pregnant out of wedlock. She didn’t want me to run off and find my birth family. Actually, it wasn’t officially an adoption until I was 16.

Can you talk about your birth mother living with your adoptive mother?

This goes back to before I was born. My birth mom became pregnant with me when she was 20. She already had two kids. Her husband was stationed in Japan in 1960, in the military. Then he was not sending any money back home. She had an affair with someone stationed at Travis Air Force Base back home here.

Lisa and William's KALX IDs, Berkeley, CA, 1985. Courtesy of William Smith.

And that’s your birth father, but you don’t know what his name is, right?

I do know his name. She told me it was Morris Phillips, but I have not been able to find him. I’ve looked at Travis Air Force records. I’m intrigued by who he is. My birth father offered to take care of me when she got pregnant with me, but she didn’t want to leave her husband. He hit her and she knocked him down the stairs. She turned down his offer and left him in the dust.

My birth mom’s father, Rev. Morrison, who had adopted her, was a prominent local pastor. He wanted her to have an abortion, so he drove her to the clinic. She refused to go in. She made him turn the car around and insisted on giving birth to me. That makes me even more pro-choice, women’s choice, period. No man should dictate. I’m pro matriarchy. Racism is a symptom of patriarchy. I believe patriarchy is the root of all evil.

So the pastor knew a woman that could take care of her and her other kids, my four-year-old sister and two-year-old brother, while she was pregnant with me. And this woman was childless, in her 50s. And she was a madam—her house was a brothel—a West Oakland Victorian. She told my mother, “You’re not going to be able to keep the child. Why don’t you give him to me and let me raise him?” That’s basically what happened.

Did you ever talk to your birth mom about how she felt about having little kids there, at the brothel? Did she think it was a safe place?

My birth mom was pregnant with me when she stayed at the brothel with my siblings. But by the time I was born my adoptive mom was no longer a madam. My birth mom told me about it years later—I didn’t know until then. My adoptive mom in her mid-50s had sugar daddies; it was a very lively community. I’ve wondered what her life was like when she was younger. She was part white, part black, with light skin. She had quite a life when younger. She looked like Billie Holiday.

My adoptive mom was also a church lady. It’s a whole different school of thought back then, you know, it’s like you did what you did. I didn’t know about the story until I was an adult in my 50s. I met my birth mom and didn’t say, “God, what did you think about that?” It was her father’s idea. She wasn’t one of the girls that worked there. She stayed in the back, and when it came time to give birth to me, they left and went to the military base in New Mexico. And then, six months later, the madam/church lady flew there, got me, and became my guardian. So, yeah, they knew each other and that’s the back story.

I also found out my birth mom was married when she was 16. She had me the day after her birthday. She’d just turned 21. She had two kids, me outside the marriage, four more with the same man as the first two, and that man had an affair and the kid who was born during it came to live with them. My birth mom’s husband had also impregnated a woman in Japan. My siblings have a Japanese sister somewhere.

The whole time I was growing up, you know, it was my mother who was keeping me from my birth mom, because she was afraid I would leave and go live with her.

Beatrice, William’s adoptive mother (left) and William and Willie, his birth mother (right). Courtesy of William Smith.

When you’re 18, after your suicide attempt, your stepdad contacted your birth mother. And did you have any idea that he even knew how to contact her?

I always use the phrase “it takes a village.” You know, the African-American migration from the South to Oakland happened in the ’40s and all their culture developed there, and people knew each other. Friends knew what happened, and there was enough to trickle down to me as rumors because my mother wouldn’t tell me.

My stepdad and my mother [Beatrice] had known each other, probably since like the ’40s and ’50s, before they got married in 1968. He knew I was adopted and had a mother out there somewhere. He didn’t know where she was or how I could contact her. But [after my suicide attempt, after Beatrice died] he said, “You need to find your mother,” meaning my birth mom. I was an only child. I was a loner. I didn’t want to be around. I was kind of aimless, and my stepfather saw me as someone who really needed tough love to get out of the house.

My adoptive mom and I were too close to the point where I’d made a suicide pact that I would follow her after she died. But weeks after my mother died, a few weeks after my attempted suicide, my birth mom called me and, I just, I picked up the phone. “Hello.”

“Hi, I’m your mom.”

I went to see her for an hour, and then I didn’t see her again for another 30 years or so because I was still loyal to my adoptive mom. My feelings might have been, at the time, kind of numb. I never had any interest in finding my birth family until I reached middle age.

And I eventually moved out, you know, and was a loner type of person who didn’t really completely fit in growing up. The whole thing didn’t come to some kind of plateau until I moved into Berkeley and got into punk rock in the early ’80s.

What was the racial make-up of your high school?

I went to Fremont High, which was predominantly black and less so Latino. It’s mostly Latino now. My adopted mom and I were moving around in Oakland back and forth, depending on the cheapest apartment she was able to rent. And finally we were in a housing project, which was, you know, only black.

We ended up in East Oakland and West Oakland, and she married an older guy [John Smith] to help raise me. He was born in 1900. He came out here to escape the Klan. He worked in sawmills, had WWII jobs, and bought a house in East Oakland. He fought a petition to keep it white. East Oakland was more idyllic in the 1970s. It was the classic crucible of American culture, funky cool. I wanted to fit in.

How did you get into punk?

I saw it on 60 Minutes, the news, and I didn’t dismiss it. I listened to white music on the radio: The Who, Led Zeppelin, Bob Dylan, Gary Numan. I liked it more than my friends, as much as funk and soul. I’d think, “Why do I like Fleetwood Mac?” My friends would criticize me, but they did like Gary Numan.

Punk rock was the way to escape from not being able to fit in as an African-American kid and not knowing how to. Interacting with people felt just awkward, and music allowed me to not worry about that. But I wasn’t cool enough to get on the bus and come all the way out to the Keystone or something. But when I dropped out of college and became a mailman, I got hired in Berkeley and moved there. Even though I was an African American from East Oakland, I decided I wanted to go work at KALX and make friends. I first went in the fall of 1984 but didn’t feel part of the clique, as a community person and not a college student. But I went back in February 1985 because I wasn’t really connecting with anybody else.

You felt ostracized growing up and embraced punk rock. Did you feel doubly ostracized at punk shows? Or did you make friends so that you could hang out or fit in or go in the pit and or whatever you want to do?

Wow, no. Alex, the same thing happened. Maybe on a smaller scale, but more and more inside. I was always awkward.

That would’ve been a pretty violent era of punk shows—hardcore.

Yeah, I had Jheri curls. And several people came up to me [assuming I was a drug dealer] and said, “Why, you don’t like drugs?”

“No, I’m actually here to see the show.”

You told me the first time you felt complete was when you met your brothers and sisters—is that right?

Yes, perfect question. And that was because of the presence of my wife, basically, you know. My wife said, “Go full circle and reconnect with your roots. You really need to find your birth family.” And that’s when I started that journey. I felt complete ’cuz I finally found black people where I didn’t feel like an outcast, because they were my family. I suddenly felt relaxed. It’s a weird feeling to find my birth family. My relationship is different to my mom than our siblings’ relationship.

How did you find them? What was it like meeting your family?

I had the birth certificate and remembered names. I did research on the internet. Certain names made sense, and I made friend requests through Facebook. When I first talked to my mom, she said it was a miracle. My mother’s voice was like Nina Simone’s. She’d say to people, “I knew I’d find him eventually.” They’d been looking for me.

After phone calls with family members, I flew up to Washington State in the fall of 2013. Lisa had said, “Get back to your roots.” I immediately bonded with my mother, and I found some things in common right away, and the family was happy to see me. They’re very close, they are middle class, living in and around Seattle.

Projects

William and Willie recording an episode for StoryCorps, 2014. Courtesy of William Smith.

Sept. 11, 2014: “William Smith (53) talks with his mother Willie Jean Dangerfield Nichols (74) about her decision to put him up for adoption and finding each other online a year ago. William describes his life growing up, his struggles with depression, and not knowing he was adopted until high school. Willie shares about making the hard decision to give her son up. Both share about their similar personalities and the circumstances around their reconnection.”

Deaths of East Oakland young men who’d bullied William in his youth.

Memorial speech for his birth mother.

Essay about trauma his adoptive mother went through.